Presbyterian Church (USA)

| Presbyterian Church (USA) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | PCUSA |

| Classification | Mainline Protestant |

| Orientation | Moderate to Progressive and Liberal |

| Theology | Reformed |

| Polity | Presbyterian |

| Co-moderators | Cecelia Armstrong and Anthony Larson |

| Exec Dir & Stated Clerk | Jihyun Oh |

| Associations | |

| Region | United States |

| Headquarters | Louisville, Kentucky |

| Origin | June 10, 1983 |

| Merger of | The Presbyterian Church in the United States and the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America |

| Separations | |

| Congregations | 8,705 (as of 2022[update])[1] |

| Members | 1,140,665 active members (2022)[1] |

| Official website | pcusa |

| a. ^ This denomination separated from PCUS before the merger. b. ^ This denomination separated from UPCUSA before the merger. | |

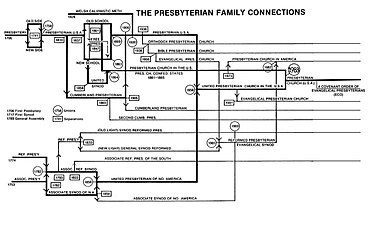

The Presbyterian Church (USA), abbreviated PCUSA, is a mainline Protestant denomination in the United States. It is the largest Presbyterian denomination in the country, known for its liberal stance on doctrine and its ordaining of women and members of the LGBT community as elders and ministers. The Presbyterian Church (USA) was established with the 1983 merger of the Presbyterian Church in the United States, whose churches were located in the Southern and border states, with the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, whose congregations could be found in every state.

The church maintains a Book of Confessions, a collection of historic and contemporary creeds and catechisms, including its own Brief Statement of Faith.[2][3] It is a member the World Communion of Reformed Churches.[4] The similarly named Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) is a separate denomination whose congregations can also trace their history to the various schisms and mergers of Presbyterian churches in the United States. Unlike the more conservative Presbyterian Church in America, the Presbyterian Church (USA) supports the ordination of women and affirms same-sex marriages. It also welcomes practicing gay and lesbian persons to serve in leadership positions as ministers, deacons, elders, and trustees.[5]

The Presbyterian Church (USA) is the largest Presbyterian denomination in the United States,[6] having 1,140,665 active members and 18,173 ordained ministers (including retired ones)[7] in 8,705 congregations at the end of 2022.[1] This number does not include members who are baptized but not confirmed, or the inactive members also affiliated.[8][9] For example, in 2005, the Presbyterian Church (USA) claimed 318,291 baptized but not confirmed members and nearly 500,000 inactive members in addition to active members.[10] Its membership has been steadily declining over the past several decades; the trend has significantly accelerated in recent years, partly due to breakaway congregations.[11][12][13] Average denominational worship attendance dropped from 748,774 in 2013 to 431,379 in 2022.[14]

Summary membership statistics for 2023 are based on only 65% of churches reporting. Reported membership based on gender: 904,780; based on age: 892,107.[15] The 2023 GA Minutes statistical volume omits the usual summary attendance statistics for synods and denomination.

The gender membership demographics show an anomalous 5% increase in men from 348,231 in 2022 to 365,632 in 2023, despite total membership decreasing by 4%. This supposed increase in men was initially reported as a notable area of growth and a reason for hope,[16] but that claim has since been removed. The church-trends database shows 384,231 male members in 2022, differing by transposing two digits, which is in line with the 4% total membership decrease from 2022 to 2023.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]Presbyterians trace their history to the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. The Presbyterian heritage, and much of its theology, began with the French theologian and lawyer John Calvin (1509–1564), whose writings solidified much of the Reformed tradition that came before him in the form of the sermons and writings of Huldrych Zwingli. From Calvin's headquarters in Geneva, the Reformed movement spread to other parts of Europe.[17] John Knox, a former Roman Catholic priest from Scotland who studied with Calvin in Geneva, took Calvin's teachings back to Scotland and led the Scottish Reformation of 1560. Because of this reform movement, the Church of Scotland embraced Reformed theology and presbyterian polity.[18] The Ulster Scots brought their Presbyterian faith with them to Ireland, where they laid the foundation of what would become the Presbyterian Church in Ireland.[19]

Immigrants from Scotland and Ireland brought Presbyterianism to North America as early as 1640, and immigration would remain a large source of growth throughout the colonial era.[20] Another source of growth were a number of New England Puritans who left the Congregational churches because they preferred presbyterian polity. In 1706, seven ministers led by Francis Makemie established the first American presbytery at Philadelphia in the Province of Pennsylvania, which was followed by the creation of the Synod of Philadelphia in 1717.[21]

The First Great Awakening and the revivalism it generated had a major impact on American Presbyterians. Ministers such as William and Gilbert Tennent, a friend of George Whitefield, emphasized the necessity of a conscious conversion experience and pushed for higher moral standards among the clergy.[22] Disagreements over revivalism, itinerant preaching, and educational requirements for clergy led to a division known as the Old Side–New Side Controversy that lasted from 1741 to 1758.[23]

In the South, the Presbyterians were evangelical dissenters, mostly Scotch-Irish, who expanded into Virginia between 1740 and 1758. Spangler in Virginians Reborn: Anglican Monopoly, Evangelical Dissent, and the Rise of the Baptists in the Late Eighteenth Century (2008)[full citation needed] argues they were more energetic and held frequent services better attuned to the frontier conditions of the colony. Presbyterianism grew in frontier areas where the Anglicans had made little impression. Uneducated whites and blacks were attracted to the emotional worship of the denomination, its emphasis on biblical simplicity, and its psalm singing.

Some local Presbyterian churches, such as Briery in Prince Edward County, owned slaves. The Briery church purchased five slaves in 1766 and raised money for church expenses by hiring them out to local planters.[24]

After the United States achieved independence from Great Britain, Presbyterian leaders felt that a national Presbyterian denomination was needed, and the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) was organized. The first general assembly was held in Philadelphia in 1789.[25] John Witherspoon, president of Princeton University and the only minister to sign the Declaration of Independence, was the first moderator.

Not all American Presbyterians participated in the creation of the PCUSA General Assembly because the divisions then occurring in the Church of Scotland were replicated in America. In 1751, Scottish Covenanters began sending ministers to America, and the Seceders were doing the same by 1753. In 1858, the majority of Covenanters and Seceders merged to create the United Presbyterian Church of North America (UPCNA).[26]

19th century

[edit]In the decades after independence many American Protestants, including Calvinists (Presbyterians and Congregationalists), Methodists, and Baptists,[27][28] were swept up in Christian revivals that would later become known as the Second Great Awakening. Presbyterians also helped to shape voluntary societies that encouraged educational, missionary, evangelical, and reforming work. As its influence grew, many non-Presbyterians feared that the PCUSA's informal influence over American life might effectively make it an established church.[29]

The Second Great Awakening divided the PCUSA over revivalism and fear that revivalism was leading to an embrace of Arminian theology. In 1810, frontier revivalists split from the PCUSA and organized the Cumberland Presbyterian Church.[30] Throughout the 1820s, support and opposition to revivalism hardened into well-defined factions, the New School and Old School respectively. By the 1838, the Old School–New School Controversy had divided the PCUSA. There were now two general assemblies each claiming to represent the PCUSA.[31]

In 1858, the New School split along sectional lines when its Southern synods and presbyteries established the pro-slavery United Synod of the Presbyterian Church.[32] Old School Presbyterians followed in 1861 after the start of hostilities in the American Civil War with the formation of the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America.[33] The Presbyterian Church in the CSA absorbed the smaller United Synod in 1864. After the war, this body was renamed the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) and was commonly nicknamed the "Southern Presbyterian Church" throughout its history.[32] In 1869, the northern PCUSA's Old School and New School factions reunited as well and was known as the "Northern Presbyterian Church".[34]

20th century to the present

[edit]

The early part of the 20th century saw continued growth in both major sections of the church. It also saw the growth of Fundamentalist Christianity (a movement of those who believed in the literal interpretation of the Bible as the fundamental source of the religion) as distinguished from Modernist Christianity (a movement holding the belief that Christianity needed to be re-interpreted in light of modern scientific theories such as evolution or the rise of degraded social conditions brought on by industrialization and urbanization).

Open controversy was sparked in 1922, when Harry Emerson Fosdick, a modernist and a Baptist pastoring a PCUSA congregation in New York City, preached a sermon entitled "Shall the Fundamentalists Win?" The crisis reached a head the following year when, in response to the New York Presbytery's decision to ordain a couple of men who could not affirm the virgin birth, the PCUSA's General Assembly reaffirmed the "five fundamentals": the deity of Christ, the Virgin Birth, the vicarious atonement, the inerrancy of Scripture, and Christ's miracles and resurrection.[35] This move against modernism caused a backlash in the form of the Auburn Affirmation — a document embracing liberalism and modernism. The liberals began a series of ecclesiastical trials of their opponents, expelled them from the church and seized their church buildings. Under the leadership of J. Gresham Machen, a former Princeton Theological Seminary New Testament professor who had founded Westminster Theological Seminary in 1929, and who was a PCUSA minister, many of these conservatives would establish what became known as the Orthodox Presbyterian Church in 1936. Although the 1930s and 1940s and the ensuing neo-orthodox theological consensus mitigated much of the polemics during the mid-20th century, disputes erupted again beginning in the mid-1960s over the extent of involvement in the civil rights movement and the issue of ordination of women, and, especially since the 1990s, over the issue of ordination of homosexuals.

Mergers

[edit]

The Presbyterian Church in the United States of America was joined by the majority of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, mostly congregations in the border and Southern states, in 1906. In 1920, it absorbed the Welsh Calvinist Methodist Church. The United Presbyterian Church of North America merged with the PCUSA in 1958 to form the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (UPCUSA).

Under Eugene Carson Blake, the UPCUSA's stated clerk, the denomination entered into a period of social activism and ecumenical endeavors, which culminated in the development of the Confession of 1967 which was the church's first new confession of faith in three centuries. The 170th General Assembly in 1958 authorized a committee to develop a brief contemporary statement of faith. The 177th General Assembly in 1965 considered and amended the draft confession and sent a revised version for general discussion within the church. The 178th General Assembly in 1966 accepted a revised draft and sent it to presbyteries throughout the church for final ratification. As the confession was ratified by more than 90% of all presbyteries, the 178th General Assembly adopted it in 1967. The UPCUSA also adopted a Book of Confessions in 1967, which would include the Confession of 1967, the Westminster Confession and Westminster Shorter Catechism, the Heidelberg Catechism, the Second Helvetic and Scots Confessions and the Barmen Declaration.[36]

An attempt to reunite the United Presbyterian Church in the USA with the Presbyterian Church in the United States in the late 1950s failed when the latter church was unwilling to accept ecclesiastical centralization. In the meantime, a conservative group broke away from the Presbyterian Church in the United States in 1973, mainly over the issues of women's ordination and a perceived drift toward theological liberalism. This group formed the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA).

Attempts at union between the churches (UPCUSA and PCUS) were renewed in the 1970s, culminating in the merger of the two churches to form the Presbyterian Church (USA) on June 10, 1983. At the time of the merger, the churches had a combined membership of 3,121,238.[37] Many of the efforts were spearheaded by the financial and outspoken activism of retired businessman Thomas Clinton who died two years before the merger.[citation needed] A new national headquarters was established in Louisville, Kentucky in 1988 replacing the headquarters of the UPCUSA in New York City and the PCUS located in Atlanta, Georgia.

The merger essentially consolidated moderate-to-liberal American Presbyterians into one body. Other US Presbyterian bodies (the Cumberland Presbyterians being a partial exception) place greater emphasis on doctrinal Calvinism, literalist hermeneutics, and conservative politics.

For the most part, PC(USA) Presbyterians, not unlike similar mainline traditions such as the Episcopal Church and the United Church of Christ, are fairly progressive on matters such as doctrine, environmental issues, sexual morality, and economic issues, though the denomination remains divided and conflicted on these issues. Like other mainline denominations, the PC(USA) has also seen a great deal of demographic aging, with fewer new members and declining membership since 1967.

Social justice initiatives and renewal movements

[edit]In the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, the General Assembly of PC(USA) adopted several social justice initiatives, which covered a range of topics including: stewardship of God's creation, world hunger, homelessness, and LGBT issues. As of 2011 the PC(USA) no longer excludes Partnered Gay and Lesbian ministers from the ministry. Previously, the PC(USA) required its ministers to remain "chastely in singleness or with fidelity in marriage." Currently, the PC(USA) permits teaching elders to perform same-gender marriages. On a congregational basis, individual sessions (congregational governing bodies) may choose to permit same-gender marriages.[38]

These changes have led to several renewal movements and denominational splinters. Some conservative-minded groups in the PC(USA), such as the Confessing Movement and the Presbyterian Lay Committee (formed in the mid-1960s)[39] have remained in the main body, rather than leaving to form new, break-away groups.

Breakaway Presbyterian denominations

[edit]Several Presbyterian denominations have split from PC(USA) or its predecessors over the years. For example, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church broke away from the Presbyterian Church in the USA (PC-USA) in 1936.

More recently formed Presbyterian denominations have attracted PC(USA) congregations disenchanted with the direction of the denomination, but wishing to continue in a Reformed, Presbyterian denomination. The Presbyterian Church in America (PCA), which does not allow ordained female clergy, separated from Presbyterian Church in the United States in 1973 and has subsequently become the second largest Presbyterian denomination in the United States. The Evangelical Presbyterian Church (EPC), which gives local presbyteries the option of allowing ordained female pastors, broke away from the United Presbyterian Church and incorporated in 1981. A PC(USA) renewal movement, Fellowship of Presbyterians (FOP) (now The Fellowship Community), held several national conferences serving disaffecting Presbyterians. FOP's organizing efforts culminated with the founding of ECO: A Covenant Order of Evangelical Presbyterians (ECO), a new Presbyterian denomination that allows ordination of women but is more conservative theologically than PC(USA).

In 2013 the presbyteries ratified the General Assembly's 2012 vote to allow the ordination of openly gay persons to the ministry and in 2014 the General Assembly voted to amend the church's constitution to define marriage as the union of two persons instead of the union of a man and woman, which was ratified (by the presbyteries) in 2015. This has led to the departure of several hundred congregations. The majority of churches leaving the Presbyterian Church (USA) have chosen to join the Evangelical Presbyterian Church or ECO. Few have chosen to join the larger more conservative Presbyterian Church in America, which does not permit female clergy.[40]

Youth

[edit]Since 1983 the Presbyterian Youth Triennium has been held every three years at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, US, and is open to Presbyterian high school students throughout the world. The very first Youth Triennium was held in 1980 at Indiana University and the conference for teens is an effort of the Presbyterian Church (USA), the largest Presbyterian denomination in the nation; Cumberland Presbyterian Church; and Cumberland Presbyterian Church in America, the first African-American denomination to embrace Presbyterianism in the reformed tradition.[41]

Since 1907, Montreat, North Carolina has hosted a youth conference every year. In 1983, Montreat Conference Center became a National Conference Center of the PC(USA) when the northern and southern denominational churches reunited.[42]

Structure

[edit]

Constitution

[edit]The Constitution of PC(USA) is composed of two portions: Part I, the Book of Confessions and Part II, the Book of Order. The Book of Confessions outlines the beliefs of the PC(USA) by declaring the creeds by which the Church's leaders are instructed and led. Complementing that is the Book of Order which gives the rationale and description for the organization and function of the Church at all levels. The Book of Order is currently divided into four sections – 1) The Foundations of Presbyterian Polity 2) The Form of Government, 3) The Directory For Worship, and 4) The Rules of Discipline.

Councils

[edit]

The Presbyterian Church (USA) has a representative form of government, known as presbyterian polity, with four levels of government and administration, as outlined in the Book of Order. The councils (governing bodies) are as follows:

- Session (of a Congregation)

- Presbytery

- Synod

- General Assembly

Session

[edit]At the congregational level, the governing body is called the session, from the Latin word sessio, meaning "a sitting". The session is made up of the pastors of the church and all elders elected and installed to active service. Following a pattern set in the first congregation of Christians in Jerusalem described in the Book of Acts in the New Testament, the church is governed by presbyters (a term and category that includes elders and Ministers of Word and Sacrament, historically also referred to as "ruling or canon elders" because they measure the spiritual life and work of a congregation and ministers as "teaching elders").[43]

The elders are nominated by a nominating committee of the congregation; in addition, nominations from the floor are permissible. Elders are then elected by the congregation. All elders elected to serve on the congregation's session of elders are required to undergo a period of study and preparation for this order of ministry, after which the session examines the elders-elect as to their personal faith; knowledge of doctrine, government, and discipline contained in the Constitution of the church, and the duties of the office of elder. If the examination is approved, the session appoints a day for the service of ordination and installation.[44] Session meetings are normally moderated by a called and installed pastor and minutes are recorded by a clerk, who is also an ordained presbyter. If the congregation does not have an installed pastor, the Presbytery appoints a minister member or elected member of the presbytery as moderator with the concurrence of the local church session.[45] The moderator presides over the session as first among equals and also serves as a "liturgical" bishop over the ordination and installation of elders and deacons within a particular congregation.

The session guides and directs the ministry of the local church, including almost all spiritual and fiduciary leadership. The congregation as a whole has only the responsibility to vote on: 1) the call of the pastor (subject to presbytery approval) and the terms of call (the church's provision for compensating and caring for the pastor); 2) the election of its own officers (elders and deacons); 3) buying, mortgaging, or selling real property. All other church matters such as the budget, personnel matters, and all programs for spiritual life and mission, are the responsibility of the session. In addition, the session serves as an ecclesiastical court to consider disciplinary charges brought against church officers or members.

The session also oversees the work of the deacons, a second body of leaders also tracing its origins to the Book of Acts. The deacons are a congregational-level group whose duty is "to minister to those who are in need, to the sick, to the friendless, and to any who may be in distress both within and beyond the community of faith." In some churches, the responsibilities of the deacons are taken care of by the session, so there is no board of deacons in that church. In some states, churches are legally incorporated and members or elders of the church serve as trustees of the corporation. However, "the power and duties of such trustees shall not infringe upon the powers and duties of the Session or of the board of deacons." The deacons are a ministry board but not a governing body.

Presbytery

[edit]

A presbytery is formed by all the congregations and the Ministers of Word and Sacrament in a geographic area together with elders selected (proportional to congregation size) from each of the congregations. Four special presbyteries are "non-geographical" in that they overlay other English-speaking presbyteries, though they are geographically limited to the boundaries of a particular synod (see below); it may be more accurate to refer to them as "trans-geographical." Three PC(USA) synods have a non-geographical presbytery for Korean language Presbyterian congregations, and one synod has a non-geographical presbytery for Native American congregations, the Dakota Presbytery. There are currently 166 presbyteries for the 8,705 congregations in the PC(USA).[46]

Only the presbytery (not a congregation, session, synod, or General Assembly) has the responsibility and authority to ordain church members to the ordered ministry of Word and Sacrament, also referred to as a Teaching Elder, to install ministers to (or remove them from) congregations as pastors, and to remove a minister from the ministry. A Presbyterian minister is a member of a presbytery. The General Assembly cannot ordain or remove a Teaching Elder, but the Office of the General Assembly does maintain and publish a national directory with the help of each presbytery's stated clerk.[47] This directory is also published bi-annually with the minutes of the General Assembly. A pastor cannot be a member of the congregation he or she serves as a pastor because his or her primary ecclesiastical accountability lies with the presbytery. Members of the congregation generally choose their own pastor with the assistance and support of the presbytery. The presbytery must approve the choice and officially install the pastor at the congregation, or approve the covenant for a temporary pastoral relationship. Additionally, the presbytery must approve if either the congregation or the pastor wishes to dissolve that pastoral relationship.

The presbytery has authority over many affairs of its local congregations. Only the presbytery can approve the establishment, dissolution, or merger of congregations. The presbytery also maintains a Permanent Judicial Commission, which acts as a court of appeal from sessions, and which exercises original jurisdiction in disciplinary cases against minister members of the presbytery.[48]

A presbytery has two elected officers: a moderator and a stated clerk. The Moderator of the presbytery is elected annually and is either a minister member or an elder commissioner from one of the presbytery's congregations. The Moderator presides at all presbytery assemblies and is the chief overseer at the ordination and installation of ministers in that presbytery.[49] The stated clerk is the chief ecclesial officer and serves as the presbytery's executive secretary and parliamentarian in accordance with the church Constitution and Robert's Rules of Order. While the moderator of a presbytery normally serves one year, the stated clerk normally serves a designated number of years and may be re-elected indefinitely by the presbytery. Additionally, an Executive Presbyter (sometimes designated as General Presbyter, Pastor to Presbytery, Transitional Presbyter) is often elected as a staff person to care for the administrative duties of the presbytery, often with the additional role of a pastor to the pastors. Presbyteries may be creative in the designation and assignment of duties for their staff. A presbytery is required to elect a Moderator and a Clerk, but the practice of hiring staff is optional. Presbyteries must meet at least twice a year, but they have the discretion to meet more often and most do.

See "Map of Presbyteries and Synods".[50]

Synod

[edit]Presbyteries are organized within a geographical region to form a synod. Each synod contains at least three presbyteries, and its elected voting membership is to include both elders and Ministers of Word and Sacrament in equal numbers. Synods have various duties depending on the needs of the presbyteries they serve. In general, their responsibilities (G-12.0102) might be summarized as: developing and implementing the mission of the church throughout the region, facilitating communication between presbyteries and the General Assembly, and mediating conflicts between the churches and presbyteries. Every synod elects a Permanent Judicial Commission, which has original jurisdiction in remedial cases brought against its constituent presbyteries, and which also serves as an ecclesiastical court of appeal for decisions rendered by its presbyteries' Permanent Judicial Commissions. Synods are required to meet at least biennially. Meetings are moderated by an elected synod Moderator with support of the synod's Stated Clerk. There are currently 16 synods in the PC(USA) and they vary widely in the scope and nature of their work. An ongoing current debate in the denomination is over the purpose, function, and need for synods.[51]

Synods of the Presbyterian Church (USA)

[edit]- Synod of Alaska-Northwest

- Synod of Boriquen (Puerto Rico)

- Synod of the Covenant

- Synod of Lakes and Prairies

- Synod of Lincoln Trails

- Synod of Living Waters

- Synod of Mid-America

- Synod of Mid-Atlantic

- Synod of the Northeast

- Synod of the Pacific

- Synod of the Rocky Mountains

- Synod of South Atlantic

- Synod of Southern California and Hawaii

- Synod of the Southwest

- Synod of the Sun

- Synod of the Trinity

See also the List of Presbyterian Church (USA) synods and presbyteries.[52]

General Assembly

[edit]The General Assembly is the highest governing body of the PC(USA). Until the 216th assembly met in Richmond, Virginia in 2004, the General Assembly met annually; since 2004, the General Assembly has met biennially in even-numbered years. It consists of commissioners elected by presbyteries (not synods), and its voting membership is proportioned with parity between elders and Ministers of Word and Sacrament. There are many important responsibilities of the General Assembly. Among them, The Book of Order lists these four:

- to set priorities for the work of the church in keeping with the church's mission under Christ

- to develop overall objectives for mission and a comprehensive strategy to guide the church at every level of its life

- to provide the essential program functions that are appropriate for overall balance and diversity within the mission of the church, and

- to establish and administer national and worldwide ministries of witness, service, growth, and development.

Elected officials

[edit]

The General Assembly elects a moderator at each assembly who moderates the rest of the sessions of that assembly meeting and continues to serve until the next assembly convenes (two years later) to elect a new moderator or co-moderator. Currently, the denomination is served by Co-Moderators Cecelia Armstrong and Anthony Larson, who were elected at the 226th General Assembly (2024). They followed Ruth Santana-Grace and Shavon Starling-Louis, elected in 2022. They followed Elona Street-Stewart and Gregory Bentley, elected in 2020.[53] At the 223rd Assembly in St Louis, MO, Co-Moderators Vilmarie Cintrón-Olivieri and Cindy Kohmann were elected. See a complete listing of past moderators at another Wikipedia Article.

A Stated Clerk of the General Assembly is elected to one or more four-year terms and is responsible for the Office of the General Assembly which conducts the ecclesiastical work of the church. The Office of the General Assembly carries out most of the ecumenical functions and all of the constitutional functions at the Assembly. The Stated Clerks since reunion are: James Andrews (1984–1996), Clifton Kirkpatrick (1996–2008), Gradye Parsons (2008–2016), J. Herbert Nelson (2016–2023), Bronwen Boswell (2023–2024) (interim), and Jihyun Oh (2024–).[54]

Bronwen Boswell was appointed Acting Stated Clerk in June 2023 to serve the remaining year of Nelson's term. She was ineligible to apply for the stated clerk position in 2024, and has limited responsibilities focused primarily on completing plans for the 2024 GA and unification of the OGA and PMA.[55] Her partial characterization of the attempted assassination of Donald Trump as "two lives lost at a Pennsylvania rally" blurs the distinction between perpetrator and victim, unlike definitions of mass shootings that often do not include the shooter in the body count.[56][third-party source needed] Bronwen's political perspective on the shooting has been contrasted with purely nonpolitical perspectives from other denominations.[57][58]

Jihyun Oh was installed in July 2024 as the Stated Clerk of the General Assembly,[59][60][61] and promoted by the Unification Commission in October 2024 to lead the interim unified agency.[62] The Unification Commission is overseeing a unification of the OGA and PMA, currently planned for summer of 2025.[63] The Committee on the Office of the General Assembly (COGA) currently has oversight over the Stated Clerk and OGA, but COGA is scheduled to be dissolved on December 31, 2024, along with the Presbyterian Mission Agency Board.[64] A new Unification Management Office is planned to manage the integration of PMA and OGA.[65] In March 2024, the former OGA Communications Director was named PCUSA Communications Director[66] and the former PMA Communications Director was named PMA Vision Integration & Constituent Service Manager.

Nelson is the first African American to be elected to the office, and is a third-generation Presbyterian pastor.[67] Nelson announced he would not seek re-election to a third term,[68] and stepped down as Stated Clerk in June 2023, a year before his second term ended.[69] Reported tensions that likely influenced the decision to resign include struggling efforts since 2016 to unify the OGA and PMA agencies, and struggling efforts to return to normal following the pandemic.[70]

The Stated Clerk is also responsible for the records of the denomination, a function formalized in 1925 when the General Assembly created the "Department of Historical Research and Conservation" as part of the Office of the General Assembly. The current "Department of History" is also known as the Presbyterian Historical Society.[71]

Structure

[edit]Six agencies carry out the work of the General Assembly, two of which (OGA and PMA) are being unified, with a new staff reporting structure that seems to imply that OGA and PMA have been dissolved. These are the Office of the General Assembly (OGA), the Presbyterian Publishing Corporation, the Presbyterian Investment and Loan Program, the Board of Pensions, the Presbyterian Foundation, and the Presbyterian Mission Agency (PMA) (formerly known as the General Assembly Mission Council).

The Board of Pensions is the oldest and largest of the PCUSA agencies, originally founded in 1717 as the Fund for Pious Uses. The Board provides those who work for congregations and affiliated ministries with healthcare, retirement, and income protection benefits. With over $12 billion in assets, the Board of Pensions is one of the largest Church Plans in the United States. The General Assembly directly elects the Board of Directors and the President. The current President is Frank Clark Spencer. In addition to its benefits program, the Board's education department runs CREDO conferences, the PCUSA's largest in service education program for ministers. The Board's Assistance Program provides financial assistance in the form of income and housing supplements, emergency grants, and debt reduction to current and retired members based on need.

The General Assembly elects members of the Presbyterian Mission Agency Board (PMAB) (formerly General Assembly Mission Council). This board is scheduled to be dissolved on December 31, 2024, by a motion approved at a specially called Unification Commission meeting on August 16, two days ahead of the planned PMAB annual retreat.[72] The timing of this motion allowed PMAB to celebrate their work in person, as their only remaining meeting, scheduled for October 29–30, 2024, was not in-person.[73] There are 30 PMAB members (20 voting; 10 non-voting).[74] The role of PMA President and Executive Director has been phased out, effective October 10–31, 2024, with both PMA and OGA staff now reporting to the Rev. Jihyun Oh, who has been named as Stated Clerk of the General Assembly and Executive Director of the Interim Unified Agency.[62] The announcement did not include any comment from the PMA President and Executive Director, or even any indication that she had been notified of the changes and agreed with the terms. Details of the leadership selection process have not been disclosed. The constitution requires maintaining an office of the Stated Clerk (Book of Order G–3.0501c), but not an office of the PMA Executive Director. The 2025 and 2026 budgets (page 18), approved by GA in July 2024, fund the office of the PMA Executive Director at $4,524,347 and $4,613,383, respectively.[75] The budget (page 26) anticipates proposing a $5 million reduction over 2 years at the Unification Commission's October 2024 meeting in order to balance. The UC announced informally at its meeting on October 11, 2024 that the budget had been scrubbed resulting in a planned small reduction in force. Jihyun Oh announced 12 layoffs, and two vacant OGA positions to remain unfilled, on November 13, 2024, with further layoffs anticipated in 2025.[76][77][78]

Previously, the General Assembly had elected the executive director of the Presbyterian Mission Agency, as the top administrator overseeing the mission work of the PC(USA). Past Executive Director of the PMA is Ruling Elder Linda Bryant Valentine(2006–2015), and Interim RE Tony De La Rosa. Elected in 2018 is Teaching Elder Diane Givens Moffett (2018–2024).

The General Assembly Permanent Judicial Commission (GAPJC) is the highest Church court of the denomination. It is composed of one member elected by the General Assembly from each of its constituent synods (16). It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Synod Permanent Judicial Commission cases involving issues of Church Constitution, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases. The General Assembly Permanent Judicial Commission issues Authoritative Interpretations of The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church (USA) through its decisions.

Affiliated seminaries

[edit]The denomination maintains affiliations with ten seminaries in the United States. These are:

- Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Austin, Texas

- Columbia Theological Seminary in Decatur, Georgia

- Johnson C. Smith Theological Seminary in Atlanta, Georgia

- Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Louisville. Kentucky

- McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago, Illinois

- Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- Princeton Theological Seminary, the first chartered by the General Assembly, in Princeton, New Jersey

- San Francisco Theological Seminary in San Anselmo, California (covenant affiliation treated as institutional affiliation)[79][80]

- Union Presbyterian Seminary in Richmond, Virginia and Charlotte, North Carolina

- University of Dubuque Theological Seminary in Dubuque, Iowa

Two other seminaries are related to the PC(USA) by covenant agreement: Auburn Theological Seminary in New York, New York, and Evangelical Seminary of Puerto Rico in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

There are numerous colleges and universities throughout the United States affiliated with PC(USA). For a complete list, see the article Association of Presbyterian Colleges and Universities. For more information, see the article PC(USA) seminaries.

While not affiliated with the PC(USA), Fuller Theological Seminary has educated many candidates for PC(USA) ministry and its former president, Mark Labberton, is an ordained minister of the PC(USA).[81]

Demographics

[edit]When the United Presbyterian Church in the USA merged with the Presbyterian Church in the United States there were 3,131,228 members. Statistics shows steadily decline since 1983. (The combined membership of the PCUS and United Presbyterian Church peaked in 1965 at 4.25 million communicant members.[82])

According to the PC(USA) data collection, active membership is defined as a member who has been confirmed, or made similar profession of faith, has been baptized, and attends regularly.[83] The reported data on active members do not include "inactive members."[84] In addition to active members, the PC(USA) archives data on members who are baptized, but not confirmed, and who are inactive. For example, in 2005, the PC(USA) reported 2.3 million active members, 318,291 baptized, but not confirmed, members, and 466,889 inactive members; the total number of members in 2005 was 3.1 million.[85]

| Year | Membership | pct change |

|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 3,100,951 | −0.98 |

| 1985 | 3,057,226 | −1.43 |

| 1986 | 3,016,488 | −1.35 |

| 1987 | 2,976,937 | −1.33 |

| 1988 | 2,938,830 | −1.30 |

| 1989 | 2,895,706 | −1.49 |

| 1990 | 2,856,713 | −1.36 |

| 1991 | 2,815,045 | −1.48 |

| 1992 | 2,780,406 | −1.25 |

| 1993 | 2,742,192 | −1.39 |

| 1994 | 2,698,262 | −1.63 |

| 1995 | 2,665,276 | −1.24 |

| 1996 | 2,631,466 | −1.28 |

| 1997 | 2,609,191 | −0.85 |

| 1998 | 2,587,674 | −0.83 |

| 1999 | 2,560,201 | −1.07 |

| 2000 | 2,525,330 | −1.38 |

| 2001 | 2,493,781 | −1.27 |

| 2002 | 2,451,969 | −1.71 |

| 2003 | 2,405,311 | −1.94 |

| 2004 | 2,362,136 | −1.83 |

| 2005 | 2,316,662 | −2.10 |

| 2006 | 2,267,118 | −2.05 |

| 2007 | 2,209,546 | −2.61 |

| 2008 | 2,140,165 | −3.23 |

| 2009 | 2,077,138 | −3.03 |

| 2010 | 2,016,091 | −3.03 |

| 2011 | 1,952,287 | −3.29 |

| 2012 | 1,849,496 | −5.26[86] |

| 2013 | 1,760,200 | −4.83[87] |

| 2014 | 1,667,767 | −5.54[88] |

| 2015 | 1,572,660 | −5.70[89] |

| 2016 | 1,482,767 | −5.71 |

| 2017 | 1,415,053 | −4.56 |

| 2018 | 1,352,678 | −4.41[90] |

| 2019 | 1,302,043 | −3.74[91] |

| 2020 | 1,245,354 | −4.35[92] |

| 2021 | 1,193,770 | −4.14[93] |

| 2022 | 1,140,665 | −4.45[1] |

| 2023 | 1,094,733 | −4.03[94] |

The PC (USA) has had the sharpest decline in their active membership among the Protestant denominations in U.S.[95] The denomination lost more than a million active members between 2005 and 2019. As of 2022, the denomination has 1,140,665 active members and about 8,705 local congregations.[1] The proposed 2025 and 2026 budgets are based on a projected 4.5% annual membership decline,[75] which projects membership of 1,089,335 (2023), 1,040,315 (2024) and 993,501 (2025). The proposed 2025 per-capita revenue of $10,133,710 at $10.20 per member is unusual, being based on projected 2025 membership, rather than the traditional 2-year lag which would apply 2023 membership. The per-capita rate is set by the General Assembly based on actual reported membership, so it is also unusual that 2023 membership was not reported in time for the 2024 General Assembly meeting.[96] As of August 2024, temporary staff is working rolls and statistics due to an extended medical leave.[97]

The average local Presbyterian Church has 131 members (the mean in 2022).[87] About 21% of the total congregations report between 1 and 25 members. Another 22% report between 26 and 50 members. Another 23% report between 51 and 100 members. The average worship attendance of a local Presbyterian congregation is 50 (38% of members). The largest congregation in the PC(USA) is Peachtree Presbyterian Church in Atlanta, Georgia, with a reported membership of 7,396 (2022). It was reported that about 32% of the Presbyterian members nationwide are over 71 years old (2022). Membership, attendance, and demographics may be skewed because about 20% of local churches representing an estimated 10% of members (generally smaller churches) did not report statistics in 2022.

Most PC(USA) members are white (89% in 2022). Other racial and ethnic members include African-Americans (4.5%), Asians (3.7%), Hispanics (1.5%), and others (1%). Despite declines in the total membership of the PC(USA), the percentage of racial-ethnic minority members has stayed about the same since 1995. The ratio of female members (61%) to male members (39%) has also remained stable since the mid-1960s.[98]

Beliefs

[edit]The Presbyterian Church (USA) adheres to Reformed theology.[99] The Book of Order of the Presbyterian Church teaches:

- The election of the people of God for service as well as for salvation;

- Covenant life marked by a disciplined concern for order in the church according to the Word of God;

- A faithful stewardship that shuns ostentation and seeks proper use of the gifts of God's creation;

- The recognition of the human tendency to idolatry and tyranny, which calls the people of God to work for the transformation of society by seeking justice and living in obedience to the Word of God” (G-2.0500).[99]

Worship

[edit]The session of the local congregation has a great deal of freedom in the style and ordering of worship within the guidelines set forth in the Directory for Worship section of the Book of Order.[100] Worship varies from congregation to congregation. The order may be very traditional and highly liturgical, or it may be very simple and informal. This variance is not unlike that seen in the "High Church" and "Low Church" styles of the Anglican Church. The Book of Order suggests a worship service ordered around five themes: "gathering around the Word, proclaiming the Word, responding to the Word, the sealing of the Word, and bearing and following the Word into the world." Prayer is central to the service and may be silent, spoken, sung, or read in unison (including the Lord's Prayer). Music plays a large role in most PC(USA) worship services and ranges from chant to traditional Protestant hymns, to classical sacred music, to more modern music, depending on the preference of the individual church and is offered prayerfully and not "for entertainment or artistic display." Scripture is read and usually preached upon. An offering is usually taken.[101]

The pastor has certain responsibilities which are not subject to the authority of the session. In a particular service of worship the pastor is responsible for:

- the selection of Scripture lessons to be read,

- the preparation and preaching of the sermon or exposition of the Bible,

- the prayers offered on behalf of the people and those prepared for the use of the people in worship,

- the music to be sung,

- the use of drama, dance, and other art forms.

The pastor may confer with a worship committee in planning particular services of worship.

— [W-1.4005]

The Directory for Worship in the Book of Order provides the directions for what must be, or may be included in worship. During the 20th century, Presbyterians were offered optional use of liturgical books:

- The Book of Common Worship of 1906

- The Book of Common Worship of 1932

- The Book of Common Worship of 1946

- The Worshipbook of 1970

- The Book of Common Worship of 1993

- The Book of Common Worship of 2018

For more information, see Liturgical book of the Presbyterian Church (USA)

In regard to vestments, the Directory for Worship leaves that decision up to the ministers. Thus, on a given Sunday morning service, a congregation may see the minister leading worship in street clothes, Geneva gown, or an alb. Among the Paleo-orthodoxy and emerging church Presbyterians, clergy are moving away from the traditional black Geneva gown and reclaiming not only the more ancient Eucharist vestments of alb and chasuble, but also cassock and surplice (typically a full-length Old English style surplice which resembles the Celtic alb, an ungirdled liturgical tunic of the old Gallican Rite).

The Service for the Lord's Day

[edit]The Service for the Lord's Day is the name given to the general format or ordering of worship in the Presbyterian Church as outlined in its Constitution's Book of Order. There is a great deal of liberty given toward worship in that denomination, so while the underlying order and components for the Service for the Lord's Day is extremely common, it varies from congregation to congregation, region to region.

Influence

[edit]

Presbyterians are among the wealthiest religious groups and are disproportionately represented in American business, law, and politics.[102][103][89] Many of the nation's oldest educational institutions, such as Princeton University, were founded by Presbyterian clergy or were associated with the Presbyterian Church.[104][105]

Historically, Presbyterians were overrepresented among American scientific elite and Nobel Prize winners.[106][107] According to Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States by Harriet Zuckerman, between 1901 and 1972, 72% of American Nobel Prize laureates have come from a Protestant background, mostly from Episcopalian, Presbyterian or Lutheran background.[107]

The Boston Brahmins, who were regarded as the nation's social and cultural elites, were often associated with the American upper class, Harvard University;[108] and the Episcopal and the Presbyterian Church.[109][110] Old money in the United States was typically associated with White Anglo-Saxon Protestant ("WASP") status,[111] particularly with the Episcopal and Presbyterian Church.[112]

Many Presbyterians have been Presidents, the latest being Ronald Reagan;[113] and they represent 13% of the U.S. Senate, despite being only 2.2% (under 0.4% as of 2021) of the general population.[114]

Presbyterians are among the wealthiest Christian denominations in the United States,[115] Presbyterians tend also to be better educated and they have a high number of graduate (64%) and post-graduate degrees (26%) per capita.[116] According to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, Presbyterians ranked as the fourth most financially successful religious group in the United States, with 32% of Presbyterians living in households with incomes of at least $100,000.[117]

Missions

[edit]The Presbyterian Church (USA) has, in the past, been a leading United States denomination in mission work, and many hospitals, clinics, colleges and universities worldwide trace their origins to the pioneering work of Presbyterian missionaries who founded them more than a century ago.

In 2008, the church supported about 215 (70 as of 2021) missionaries abroad annually.[118] Many churches sponsor missionaries abroad at the session level (the local church level), and these are not included in official statistics.

A vital part of the world mission emphasis of the denomination is building and maintaining relationships with Presbyterian, Reformed and other churches around the world, even if this is not usually considered missions.

The PC(USA) is a leader in disaster assistance relief and also participates in or relates to work in other countries through ecumenical relationships, in what is usually considered not missions, but deaconship.

Ecumenical relationships and full communion partnerships

[edit]The General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA) determines and approves ecumenical statements, agreements, and maintains correspondence with other Presbyterian and Reformed bodies, other Christians churches, alliances, councils, and consortia. Ecumenical statements and agreements are subject to the ratification of the presbyteries. The following are some of the major ecumenical agreements and partnerships.

The church is committed to "engage in bilateral and multilateral dialogues with other churches and traditions in order to remove barriers of misunderstanding and establish common affirmations."[119] As of 2012 it is in dialogue with the Episcopal Church, the Moravian Church, the Korean Presbyterian Church in America, the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in America, and the US Conference of Catholic Bishops. It also participates in international dialogues through the World Council of Churches and the World Communion of Reformed Churches. The most recent international dialogues include Pentecostal churches, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Orthodox Church in America, and others.

In 2011 the National Presbyterian Church in Mexico, in 2012 the Mizoram Presbyterian Church[120] and in 2015 the Independent Presbyterian Church of Brazil along with the Evangelical Presbyterian and Reformed Church in Peru severed ties with the PCUSA because of the PCUSA's teaching with regard to homosexuality.[121]

National and international ecumenical memberships

[edit]The Presbyterian Church (USA) is in corresponding partnership with the National Council of Churches, the World Communion of Reformed Churches,[122] and the World Council of Churches. It is a member of Churches for Middle East Peace.

Formula of agreement

[edit]

In 1997 the PCUSA and three other churches of Reformation heritage: the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the Reformed Church in America and the United Church of Christ, acted on an ecumenical proposal of historic importance, known as A Formula of Agreement. The timing reflected a doctrinal consensus which had been developing over the past thirty-two years coupled with an increasing urgency for the church to proclaim a gospel of unity in contemporary society. In light of identified doctrinal consensus, desiring to bear visible witness to the unity of the Church, and hearing the call to engage together in God's mission, it was recommended:

That the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the Presbyterian Church (USA), the Reformed Church in America, and the United Church of Christ declare on the basis of A Common Calling and their adoption of this A Formula of Agreement that they are in full communion with one another. Thus, each church is entering into or affirming full communion with three other churches.[123]

— Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) Book of Order (2009/2011), C-1

The term "full communion" is understood here to specifically mean that the four churches:

- recognize each other as churches in which the gospel is rightly preached and the sacraments rightly administered according to the Word of God;

- withdraw any historic condemnation by one side or the other as inappropriate for the life and faith of our churches today;

- continue to recognize each other's Baptism and authorize and encourage the sharing of the Lord's Supper among their members; recognize each other's various ministries and make provision for the orderly exchange of ordained ministers of Word and Sacrament;

- establish appropriate channels of consultation and decision-making within the existing structures of the churches;

- commit themselves to an ongoing process of theological dialogue in order to clarify further the common understanding of the faith and foster its common expression in evangelism, witness, and service;

- pledge themselves to living together under the Gospel in such a way that the principle of mutual affirmation and admonition becomes the basis of a trusting relationship in which respect and love for the other will have a chance to grow.

The agreement assumed the doctrinal consensus articulated in A Common Calling:The Witness of Our Reformation Churches in North America Today, and is to be viewed in concert with that document. The purpose of A Formula of Agreement is to elucidate the complementarity of affirmation and admonition as the basic principle of entering into full communion and the implications of that action as described in A Common Calling.

The 209th General Assembly (1997) approved A Formula of Agreement and in 1998 the 210th General Assembly declared full communion among these Protestant bodies.

World Communion of Reformed Churches

[edit]As of June 2010,[update] the World Alliance of Reformed Churches merged with the Reformed Ecumenical Council to form the World Communion of Reformed Churches. The result was a form of full communion similar to that outline in the Formula of Agreement, including orderly exchange of ministers.

Churches Uniting in Christ

[edit]The PC(USA) is one of nine denominations that joined to form the Consultation on Church Union, which initially sought a merger of the denominations. In 1998 the Seventh Plenary of the Consultation on Church Union approved a document "Churches in Covenant Communion: The Church of Christ Uniting" as a plan for the formation of a covenant communion of churches. In 2002 the nine denominations inaugurated the new relationship and became known as Churches Uniting in Christ. The partnership is considered incomplete until the partnering communions reconcile their understanding of ordination and devise an orderly exchange of clergy.

Controversies

[edit]Homosexuality

[edit]

Paragraph G-6.0106b of the Book of Order, which was adopted in 1996, prohibited the ordination of those who were not faithful in heterosexual marriage or chaste in singleness. This paragraph was included in the Book of Order from 1997 to 2011, and was commonly referred to by its pre-ratification designation, "Amendment B".[124] Several attempts were made to remove this from the Book of Order, ultimately culminating in its removal in 2011. In 2011, the Presbyteries of the PC(USA) passed Amendment 10-A permitting congregations to ordain openly gay and lesbian elders and deacons, and allowing presbyteries to ordain ministers without reference to the fidelity/chastity provision, saying "governing bodies shall be guided by Scripture and the confessions in applying standards to individual candidates".[125]

Many Presbyterian scholars, pastors, and theologians have been heavily involved in the debate over homosexuality over the years. The Presbyterian Church of India's cooperation with the Presbyterian Church (USA) was dissolved in 2012 when the PC(USA) voted to ordain openly gay clergy to the ministry.[126] In 2012, the PC(USA) granted permission, nationally, to begin ordaining openly gay and lesbian clergy.[127]

Since 1980, the More Light Churches Network has served many congregations and individuals within American Presbyterianism who promote the full participation of all people in the PC(USA) regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity. The Covenant Network of Presbyterians was formed in 1997 to support repeal of "Amendment B" and to encourage networking among like-minded clergy and congregations.[128] Other organizations of Presbyterians, such as the Confessing Movement and the Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals, have organized on the other side of the issue to support the fidelity/chastity standard for ordination, which was removed in 2011.

The Presbyterian Church (USA) voted to allow same-sex marriages on June 19, 2014, during its 221st General Assembly, making it one of the largest Christian denominations in the world to allow same-sex unions. This vote lifted a previous ban, and allows pastors to perform marriages in jurisdictions where it is legal. Additionally, the Assembly approved amending the Book of Order that would change the definition of marriage from "between a man and a woman" to "between two people, traditionally between a man and a woman".

General Assembly 2006

[edit]The 2006 Report of the Theological Task Force on Peace, Unity, and Purity of the Church,[129] in theory, attempted to find common ground. Some felt that the adoption of this report provided for a clear local option mentioned, while the Stated Clerk of the General Assembly, Clifton Kirkpatrick went on record as saying, "Our standards have not changed. The rules of the Book of Order stay in force and all ordinations are still subject to review by higher governing bodies." The authors of the report stated that it is a compromise and return to the original Presbyterian culture of local controls. The recommendation for more control by local presbyteries and sessions is viewed by its opposition as a method for bypassing the constitutional restrictions currently in place concerning ordination and marriage, effectively making the constitutional "standard" entirely subjective.

In the General Assembly gathering of June 2006, Presbyterian voting Commissioners passed an "authoritative interpretation", recommended by the Theological Task Force, of the Book of Order (the church constitution). Some argued that this gave presbyteries the "local option" of ordaining or not ordaining anyone based on a particular presbytery's reading of the constitutional statute. Others argued that presbyteries have always had this responsibility and that this new ruling did not change but only clarified that responsibility. On June 20, 2006, the General Assembly voted 298 to 221 (or 57% to 43%) to approve such interpretation. In that same session on June 20, the General Assembly also voted 405 to 92 (with 4 abstentions) to uphold the constitutional standard for ordination requiring fidelity in marriage or chastity in singleness.

General Assembly 2008

[edit]The General Assembly of 2008 took several actions related to homosexuality. The first action was to adopt a different translation of the Heidelberg Catechism from 1962, removing the words "homosexual perversions" among other changes. This will require the approval of the 2010 and 2012 General Assemblies as well as the votes of the presbyteries after the 2010 Assembly.[needs update][130] The second action was to approve a new Authoritative Interpretation of G-6.0108 of the Book of Order allowing for the ordaining body to make decisions on whether or not a departure from the standards of belief of practice is sufficient to preclude ordination.[131] Some argue that this creates "local option" on ordaining homosexual persons. The third action was to replace the text of "Amendment B" with new text: "Those who are called to ordained service in the church, by their assent to the constitutional questions for ordination and installation (W-4.4003), pledge themselves to live lives obedient to Jesus Christ the Head of the Church, striving to follow where he leads through the witness of the Scriptures, and to understand the Scriptures through the instruction of the Confessions. In so doing, they declare their fidelity to the standards of the Church. Each governing body charged with examination for ordination or installation (G-14.0240 and G-14.0450) establishes the candidate's sincere efforts to adhere to these standards."[132] This would have removed the "fidelity and chastity" clause. This third action failed to obtain the required approval of a majority of the presbyteries by June 2009. Fourth, a resolution was adopted to affirm the definition of marriage from Scripture and the Confessions as being between a man and a woman.[133]

General Assembly 2010

[edit]In July 2010, by a vote of 373 to 323, the General Assembly voted to propose to the presbyteries for ratification a constitutional amendment to remove from the Book of Order section G-6.0106.b. which included this explicit requirement for ordination: "Among these standards is the requirement to live either in fidelity within the covenant of marriage between a man and a woman (W-4.9001), or chastity in singleness." This proposal required ratification by a majority of the 173 presbyteries within 12 months of the General Assembly's adjournment.[134][135] A majority of presbytery votes was reached in May 2011. The constitutional amendment took effect July 10, 2011.[136] This amendment shifted back to the ordaining body the responsibility for making decisions about whom they shall ordain and what they shall require of their candidates for ordination. It neither prevents nor imposes the use of the so-called "fidelity and chastity" requirement, but it removes that decision from the text of the constitution and places that judgment responsibility back upon the ordaining body where it had traditionally been prior to the insertion of the former G-6.0106.b. in 1997. Each ordaining body, the session for deacon or elder and the presbytery for minister, is now responsible to make its own interpretation of what scripture and the confessions require of ordained officers.

General Assembly 2014

[edit]In June 2014, the General Assembly approved a change in the wording of its constitution defining marriage as a contract "between a woman and a man" to that of a contract "between two people, traditionally a man and a woman". It allowed gay and lesbian weddings within the church and further allowed clergy to perform same-sex weddings. That revision gave clergy the choice of whether or not to preside over same-sex marriages; clergy were not compelled to perform same-sex marriages.

Property ownership

[edit]PC(USA)'s book of order includes a "trust clause", which grants ownership of church property to the presbytery. Under this trust clause, the presbytery may assert a claim to the property of the congregation in the event of a congregational split, dissolution (closing), or disassociation from the PC(USA). This clause does not prevent particular churches from leaving the denomination, but if they do, they may not be entitled to any physical assets of that congregation unless by agreement with the presbytery. Recently this provision has been vigorously tested in courts of law.

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

[edit]In June 2004, the General Assembly met in Richmond, Virginia, and adopted by a vote of 431–62 a resolution that called on the church's committee on Mission Responsibility through Investment (MRTI) "to initiate a process of phased, selective divestment in multinational corporations operating in Israel". The resolution also said "the occupation ... has proven to be at the root of evil acts committed against innocent people on both sides of the conflict".[137] The church statement at the time noted that "divestment is one of the strategies that U.S. churches used in the 1970s and 80s in a successful campaign to end apartheid in South Africa".

A second resolution, calling for an end to the construction of a wall by the state of Israel, passed.[138] The resolution opposed to the construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier, regardless of its location, and opposed the United States government making monetary contribution to the construction. The General Assembly also adopted policies rejecting Christian Zionism and allowing the continued funding of conversionary activities aimed at Jews. Together, the resolutions caused tremendous dissent within the church and a sharp disconnect with the Jewish community. Leaders of several American Jewish groups communicated to the church their concerns about the use of economic leverages that apply specifically to companies operating in Israel.[139] Some critics of the divestment policy accused church leaders of anti-Semitism.[140][141][142]

In June 2006, after the General Assembly in Birmingham, Alabama changed policy (details), both pro-Israel and pro-Palestinian groups praised the resolution. Pro-Israel groups, who had written General Assembly commissioners to express their concerns about a corporate engagement/divestment strategy focused on Israel,[143] praised the new resolution, saying that it reflected the church stepping back from a policy that singled out companies working in Israel.[144] Pro-Palestinian groups said that the church maintained the opportunity to engage and potentially divest from companies that support the Israeli occupation, because such support would be considered inappropriate according to the customary MRTI process.

In August 2011, the American National Middle Eastern Presbyterian Caucus (NMEPC) endorsed the boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) campaign against Israel.[145]

In January 2014, The PC(USA) published "Zionism unsettled", which was commended as "a valuable opportunity to explore the political ideology of Zionism".[146] One critic claimed it was anti-Zionist and characterized the Israeli–Palestinian as a conflict fueled by a "pathology inherent in Zionism".[147] The Simon Wiesenthal Center described the study guide as "a hit-piece outside all norms of interfaith dialogue. It is a compendium of distortions, ignorance and outright lies – that tragically has emanated too often from elites within this church".[148] The PC(USA) subsequently withdrew the publication from sale on its website.[149]

On June 20, 2014, the General Assembly in Detroit approved a measure (310–303) calling for divestment from stock in Caterpillar, Hewlett-Packard and Motorola Solutions in protest of Israeli policies on the West Bank. The vote was immediately and sharply criticized by the American Jewish Committee which accused the General Assembly of acting out of anti-Semitic motives. Proponents of the measure strongly denied the accusations.[150]

In June 2022, at its 225th General Assembly, the church's Committee on International Engagement voted to declare Israel an apartheid state and designate Nakba Day. The committee also called for an end to Israel's blockade of the Gaza Strip and affirmed the "right of all people to live and worship peacefully" in Jerusalem.[151]

List of notable congregations

[edit]- Independent Presbyterian Church in Birmingham, Alabama[152]

- Bel Air Presbyterian Church in Bel Air, California

- Brick Presbyterian Church (New York City)

- Church of the Covenant (Boston)

- Church of the Pilgrims (Washington DC)

- the Cathedral of Hope (Pittsburgh), also known as East Liberty Presbyterian Church[153]

- Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church (Manhattan)

- First Presbyterian Church (Charlotte, North Carolina)[154]

- First Presbyterian Church of Dallas (Dallas, Texas)

- First Presbyterian Church (Manhattan)

- First Presbyterian Church (Nashville, Tennessee)

- First Presbyterian Church (Philadelphia)

- First Presbyterian Church (Springfield, Illinois)

- Fort Street Presbyterian Church (Detroit, Michigan)

- Fort Washington Presbyterian Church

- Fourth Presbyterian Church (Chicago)

- Highland Presbyterian Church (Kentucky)

- Idlewild Presbyterian Church in Memphis, Tennessee

- Kirk in the Hills (Bloomfield Township, Oakland County)

- Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church (New York City)

- Myers Park Presbyterian Church (Charlotte, North Carolina)

- National Presbyterian Church (Washington, District of Columbia)

- Old Pine Street Church (Philadelphia)

- Peachtree Presbyterian Church (Atlanta)

- Rutgers Presbyterian Church (New York City)

- Second Presbyterian Church (Indianapolis, Indiana)

- Second Presbyterian Church (Nashville, Tennessee)

- Shadyside Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh

- University Presbyterian Church (Seattle, Washington)

- Village Presbyterian Church (Prairie Village, Kansas)

- Webster Groves Presbyterian Church (St. Louis, MO)

- Westminster Presbyterian Church (Los Angeles)

- Westminster Presbyterian Church (Minneapolis)

- West-Park Presbyterian Church (Manhattan)

- Woods Memorial Presbyterian Church (Severna Park, Maryland)

See also

[edit]- Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church

- Association of Presbyterian Colleges and Universities

- Churches Uniting in Christ

- Cumberland Presbyterian Church

- Evangelical Presbyterian Church (United States)

- Ghost Ranch

- Ordination exams

- Orthodox Presbyterian Church

- Presbyterian Church in America

- Presbyterian Church (USA) Hezbollah controversy

- Reformed Churches in North America

- Religion in Louisville, Kentucky

- Protestantism in the United States

- Christianity in the United States

- Category:American Presbyterians

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Jones, Rick (May 1, 2023). "PC(USA) church membership still in decline". pcusa.org. Archived from the original on May 1, 2023. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ "Confessions". Presbyterian Mission Agency. Archived from the original on February 6, 2024. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church(USA)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ "Ecumenical Partners and Dialogue – PC(USA) OGA". Archived from the original on February 6, 2024. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ "US Presbyterian church recognizes gay marriage". BBC News. March 18, 2015. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Hawley, George (2017). Demography, Culture, and the Decline of America's Christian Denominations. Lexington Books. pp. 178–179.

- ^ "PC(USA) Research Services – Church Trends – Five Years at a Glance: Elders". Research Services, Presbyterian Mission Agency. PC(USA). Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) – News & Announcements – Once a ruling elder, always a ruling elder". Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). August 6, 2013. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ "Clerks Corner: Categories of Membership, Defined by the Book of Order G-1.04". Presbytery of Philadelphia. January 13, 2017. Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- ^ "PC(USA) membership down, financial giving up". The Presbyterian Outlook. June 26, 2006. Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- ^ "Comparative Statistics". Research Services, Presbyterian Mission Agency. PC(USA). 2012. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012.

- ^ "Addressing the Rumor that the PCUSA Is Going Out of Business Anytime Soon". The Aquila Report. December 19, 2012. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ Weston, William J. (2008). "Rebuilding the Presbyterian Establishment" (PDF). Office of Theology and Worship. PC(USA). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2023. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ "PC(USA) Research Services – Church Trends". Research Services, Presbyterian Mission Agency. PC(USA). Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "COMPARATIVE SUMMARIES OF STATISTICS" (PDF). presbyterianmission.org. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ^ "While overall PC(USA) membership continues to decline, new worshiping communities maintain their growth".

- ^ "History of the Church". Presbyterian Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ "John Knox: Scottish Reformer". Presbyterian Historical Society. October 2, 2014. Archived from the original on January 6, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ "About Us". Presbyterian Church of Ireland. Archived from the original on February 28, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ Hall 1982, pp. 101.

- ^ Longfield 2013, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Longfield 2013, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Longfield 2013, pp. 15.

- ^ Oast 2010, pp. 867.

- ^ Longfield 2013, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Hall 1982, pp. 106.

- ^ "22c. Religious Transformation and the Second Great Awakening". USHistory.org. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ Hammond, Paul. "From Calvinism to Arminianism: Baptists and the Second Great Awakening (1800–1835)" (PDF). Baylor.edu. Oklahoma Baptist University. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

"Baptists were actively involved in the initial phases of both the rural and urban revival practices, even though the Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and Methodists were the leaders.

- ^ Longfield 2013, p. 54.

- ^ Longfield 2013, pp. 57, 139.

- ^ Longfield 2013, p. 92.

- ^ a b Hall 1982, pp. 111.

- ^ Longfield 2013, pp. 108.

- ^ Longfield 2013, pp. 114–115.

- ^ D.G. Hart & John Muether Seeking a Better Country: 300 Years of American Presbyterianism (P&R Publishing, 2007) pg. 192

- ^ Hart & Meuther, p. 217

- ^ Kibler, Craig M. PCUSA projects largest membership loss ever in 2007 Archived June 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Presbyterian Layman, February 19, 2008.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions: Civil Union and Marriage" (PDF). Pcusa.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ^ "The history of the Presbyterian Lay Committee". layman.org. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Not just gay issues: Why hundreds of congregations made final break with mainline denominations – Ahead of the Trend". Blogs.thearda.com. November 24, 2014. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ "Presbyterian (USA) Youth Triennium 2013". Presbyterianyouthtriennium.org. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ "History". Montreat Conference Center. January 31, 2018. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ "Undivided Plural Ministries", Theology & worship (PDF), PC(USA), archived from the original (PDF) on August 11, 2009

- ^ General Assembly 2009, G-14.0240.

- ^ General Assembly 2009, G-9.0202b.

- ^ Administrative Commission on Mid Councils approves presbytery reorganization for New Jersey, PC(USA), March 8, 2021, archived from the original on July 12, 2021, retrieved July 12, 2021

- ^ Online Minister Directory, PC(USA), archived from the original on July 21, 2021, retrieved June 30, 2021

- ^ General Assembly 2009, The Rules of Discipline.

- ^ General Assembly 2009, The Rules of Discipline W-4.4003.

- ^ "Links", Oga, PC(USA), archived from the original on January 8, 2012, retrieved February 28, 2012

- ^ "Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) - Whither synods?". March 19, 2013.

- ^ Mid-council listing, 2018–19, Synods and Presbyteries, PC(USA) Organisation of the General Assembly, September 13, 2018, archived from the original on July 9, 2021

- ^ "224th General Assembly (2020)". PC(USA) Office of the General Assembly. Archived from the original on August 5, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Decently But Not Always in Good Order: An Historical Overview of Choosing the PC(USA) Stated Clerk". history.pcusa.org. May 13, 2016. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ "Stated clerk ends historic term in historic fashion". The Presbyterian Outlook. June 30, 2023. Archived from the original on October 16, 2023. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) - Acting Stated Clerk condemns violence at Trump rally". pcusa.org. July 15, 2024. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ^ Novick, Quinn (July 17, 2024). "Church Officials' Prayers Follow Trump Shooting". Juicy Ecumenism.

- ^ "A Family and a Global Methodist Local Church Lose a Faithful Member in Assassination Attempt - Making Disciples of Jesus". The Global Methodist Church. July 16, 2024. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) - the Rev. Jihyun Oh is elected, then installed, as Stated Clerk of the General Assembly of the PC(USA)". July 2024.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) – The Rev. Jihyun Oh is the nominee to be the next Stated Clerk of the General Assembly". pcusa.org. April 26, 2024. Archived from the original on April 26, 2024. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) – Stated Clerk of the General Assembly candidate interviews". pcusa.org. January 22, 2024. Archived from the original on January 22, 2024. Retrieved January 22, 2024.