Oath of Supremacy

The Oath of Supremacy required any person taking public or church office in the Kingdom of England, or in its subordinate Kingdom of Ireland, to swear allegiance to the monarch as Supreme Governor of the Church. Failure to do so was to be treated as treasonable. The Oath of Supremacy was originally imposed by King Henry VIII of England through the Act of Supremacy 1534, but repealed by his elder daughter, Queen Mary I of England, and reinstated under Henry's other daughter and Mary's half-sister, Queen Elizabeth I of England, under the Act of Supremacy 1558. The Oath was later extended to include Members of Parliament (MPs) and people studying at universities. In 1537, the Irish Supremacy Act was passed by the Parliament of Ireland, establishing Henry VIII as the supreme head of the Church of Ireland. As in England, a commensurate Oath of Supremacy was required for admission to offices.

In 1801, retained by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the oath continued to bar Catholics from Parliament until substantially amended by the Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1829. The requirement to take the oath for Oxford University students was not removed until the Oxford University Act 1854.

The oath was finally repealed in 1969 by Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969.

Text

[edit]As published in 1535, the oath read – repealed in 1589 by Act of Supremacy 1558:

I, [name] do utterly testifie and declare in my Conscience, that the Kings Highnesse is the onely Supreame Governour of this Realme, and all other his Highnesse Dominions and Countries, as well in all Spirituall or Ecclesiasticall things or causes, as Temporall: And that no forraine Prince, Person, Prelate, State or Potentate, hath or ought to have any Jurisdiction, Power, Superiorities, Preeminence or Authority Ecclesiasticall or Spirituall within this Realme. And therefore, I do utterly renounce and forsake all Jurisdictions, Powers, Superiorities, or Authorities; and do promise that from henchforth I shall beare faith and true Allegiance to the Kings Highnesse, his Heires and lawfull Successors: and to my power shall assist and defend all Jurisdictions, Privileges, Preheminences and Authorities granted or belonging to the Kings Highnesse, his Heires and Successors or united and annexed to the Imperial Crowne of the Realme: so helpe me God: and by the Contents of this Booke.[1]

In 1559, it was published as follows – repealed in 1969 by Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969:

I, A. B., do utterly testify and declare in my conscience that the Queen's Highness is the only supreme governor of this realm, and of all other her Highness's dominions and countries, as well in all spiritual or ecclesiastical things or causes, as temporal, and that no foreign prince, person, prelate, state or potentate hath or ought to have any jurisdiction, power, superiority, pre-eminence or authority ecclesiastical or spiritual within this realm; and therefore I do utterly renounce and forsake all foreign jurisdictions, powers, superiorities and authorities, and do promise that from henceforth I shall bear faith and true allegiance to the Queen's Highness, her heirs and lawful successors, and to my power shall assist and defend all jurisdictions, pre-eminences, privileges and authorities granted or belonging to the Queen's Highness, her heirs or successors, or united or annexed to the imperial crown of this realm. So help me God, and by the contents of this Book.[2]

Punishment

[edit]Roman Catholics who refused to take the Oath of Supremacy were indicted for treason on charges of praemunire. For example, Sir Thomas More opposed the King's separation from the Roman Catholic Church in the English Reformation and refused to accept him as Supreme Head of the Church of England, a title which had been given by parliament through the Act of Supremacy of 1534. He was imprisoned in 1534 for his refusal to take the oath, because the act discredited papal authority, and his refusal to accept the annulment of Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. In 1535, he was tried for treason, convicted on perjured testimony, and beheaded.[3][4]

Exceptions and retention

[edit]Under the reigns of Charles II and James II, the Oath of Supremacy was not so widely employed by the Crown. This was largely due to the Catholic sympathies and practices of these monarchs, and the resulting high number of Roman Catholics serving in official positions. Examples of officials who never had to take the Oath include the Catholic Privy Counsellors, Sir Stephen Rice and Justin McCarthy, Viscount Mountcashel. The centrality of the Oath was re-established under the reign of William III and Mary II, following the Glorious Revolution, and in Ireland following the Williamite reconquest. The Oath was retained in the Acts of Union 1800 that transferred Irish representation, still wholly Protestant, from the Irish Parliament in Dublin to the Westminster parliament, reconstituted as the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Abolition for MPs

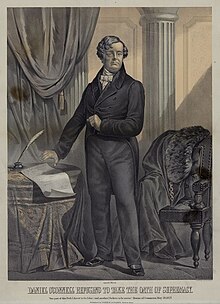

[edit]In 1828, the Irish Catholic leader Daniel O'Connell defeated William Vesey-FitzGerald in a parliamentary by-election in County Clare. His triumph, as the first Catholic to be returned in a parliamentary election since 1688, made a clear issue of the oath, as it required that MPs acknowledge the King as "Supreme Governor" of the Church and thus forswear the Roman communion. Fearful of the widespread disturbances that might follow from continuing to insist on the letter of the oath, the government finally relented. With the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, persuading the King, George IV, and the Home Secretary, Sir Robert Peel, engaging the Whig opposition, the Catholic Relief Act became law in 1829.[5]

See also

[edit]- Oath of Allegiance (United Kingdom)

- Elizabethan Religious Settlement

- Religion in the United Kingdom

- Augustine Webster

References

[edit]- ^ Cromwell, Thomas (25 February 2012). "Oath of Supremacy 1535 (Actual Text/ Sir Thomas Audley)". queenanneboleyn.com. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Life in Elizabethan England 21: More Religion". Elizabethan.org. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ (Saint), Sir Thomas More (2004). A Thomas More Source Book. CUA Press. ISBN 9780813213767.

- ^ Wilde, Lawrence (12 August 2016). Thomas More's Utopia: Arguing for Social Justice. Routledge. ISBN 9781317281375.

- ^ Bloy, Marjorie (2011). "The Peel Web-Wellington's speeches on Catholic Emancipation". A Web of English History. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2011.